Tom Read tells PublicTechnology Live about GDS’s plans to drive transformation into its second decade, and how the agency’s future priorities were informed by its peers in Ukraine

Credit: Crown Copyright/Open Government Licence v3.0

The UK government must work to catch up to other countries in making digital public services personalised and mobile-first, according to the chief executive of the Government Digital Service.

Thanks in large part to work led by GDS in its early years of existence, in the middle part of the last decade the UK was ranked as the world’s leading digital government, in rankings published biennially by the UN. In the last two publications of the global report – in 2018 and 2020 – the country’s position slipped to fourth, and then seventh.

Delivering the opening keynote presentation at PublicTechnology Live this week, GDS head Tom Read (pictured above) told attendees that the nations that have now overtaken the UK are those that have led the way in responding to two key shifts that are taking place in digital public services.

“The best digital nations in the world have adapted – Singapore, Denmark, Estonia, South Korea – they have pivoted and put things mobile first and they have made them hyperpersonalised for people,” he said. “We need to really look at these trends: mobile and hyperpersonalisation.”

Read, who rejoined GDS last year as CEO, praised some digital services – such as applying for a passport, sending money to prison, and the NHS app – and said now is the time for others to catch up.

Related content

- Government-wide login system due to start public testing this month

- Departmental plans to include transformation commitments

- Minister on plan for government digital tools that ‘serve users proactively – rather than reactively’

“For every good service that we have, we have a service that doesn’t actually work on a mobile and hasn’t been touched in 15 years – for good reasons – or a service that is really good on the front end, but you still need to go and find a printer and post it in,” he said. “Or [there are some] services that are not really written in English – they are written in lawyer… [and] are almost impenetrable for users. Or there are services that ask you send in information that the government already has on you, because it’s too difficult for us to ask another department for that information. That’s putting an extra burden on the system and the users.”

The GDS boss added: “Other services are really easy to use but then you’ve got to wait weeks or months for the service to come through. We need to work out how we use the data, the information we have across government to make that better. We can’t just fix the front end. There is an awful lot to do.”

Learning from Ukraine

It is now 10 years since both GDS and the gov.uk site were first launched.

Read described meeting Mykhailo Fedorov, digital transformation minister of Ukraine, last July, as an important moment in highlighting how user habits have changed and what the UK government needs to do to adapt.

The minister came over to the UK to share what he was doing to make Ukraine “the most digital nation on earth”, Read said.

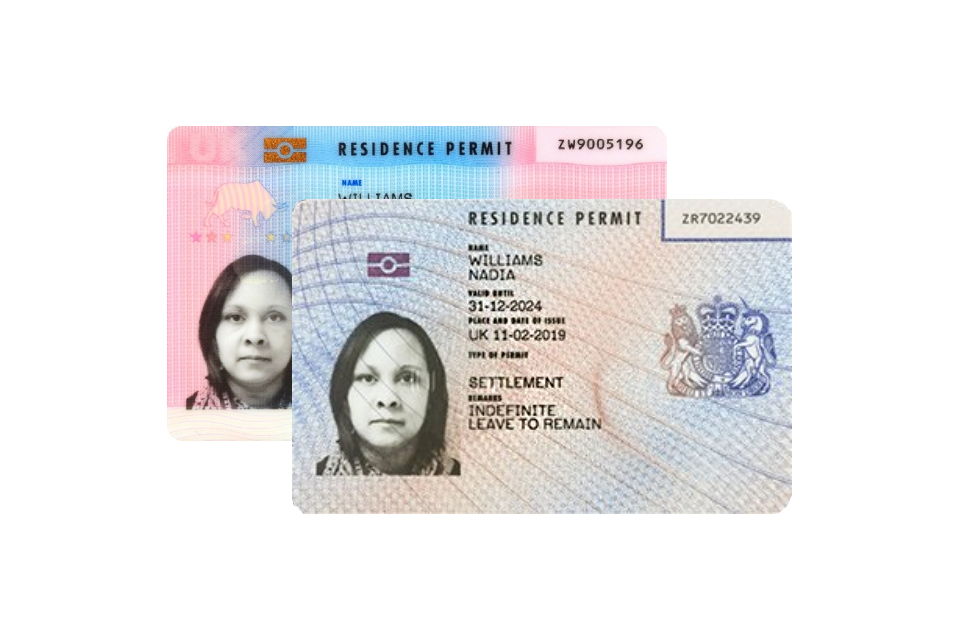

“It started very formal with his advisors and people giving a background and then, suddenly, he just wanted to show us; he got his phone out of his pocket and he got us all crowded around – including the ministers – and he showed on his phone how he had his ID and passport and his driver’s licence and he could get instant access to this list of services, because they already knew who he was.

“They had his identity and you could instantly click and access services. After the meeting, our minister at the time, Julia Lopez, ran up to me and said: ‘that’s what I want for digital government – when can you do it?’.”

He added: “That’s kind of like the North Star for digital transformation in government: how can you make it so seamless that you don’t need to think, you just use the data government already has? Because we know so much about you already. It’s much harder than it sounds.”

“For every good service that we have, we have a service that doesn’t actually work on a mobile and hasn’t been touched in 15 years – for good reasons – or a service that is really good on the front end, but you still need to go and find a printer and post it in.”

Tom Read, GDS

In 2016, 35% of gov.uk use came from mobile devices – a figure which had risen to 65% in 2021.

“But more importantly, for people on low incomes, 90% of them use a mobile phone and, if you look at the type of phone they are using, very few of them are using the latest iPhone: they are usually using a multiple-years-out-of-date Android phone. That’s how users are using internet services now,” Read said.

“This was minister Fedorov’s point: have everything on your phone, because that’s where people are,” he added.

Appy talk

Read said the government needs to look to provide more of its own apps – which represents a reversal of the policy explicitly set out by former leaders of GDS during in its early years in operation.

While such an approach is “absolutely right in 2014”, it is “not necessarily the case now”, he told the PublicTechnology Live audience.

He picked out several core objectives for GDS in the next few years:

- Make it easier for people to find what they are looking for

- Make it simple for people to prove their identity so they can access any government service

- Help departments to transform all of their services to be digital by default

Making it easier for people to prove their identity could be a “Trojan horse for hyperpersonalisation”, Read said. Government is already making “steps in the right direction” to personalise services to the specific needs of individuals, he added. But there are 20% of people who have no form of identity, such as a passport or driving licence, and the “hard bit” will be making digital work for them.

GDS is currently engaged in delivering a new government-wide login platform, including a GOV.UK app through which citizens will be to access a comprehensive range of services. A key objective of the programme – as described by Read last year to parliament’s Public Accounts Committee – is to create a platform that serves all users as equally as possible, including those whose identity it may be more complicated for the government to verify, due to a lack of documentation or financial records.