For governments and armed forces around the world, the digital domain has become a potential battlefield. But this new realm of warfare brings with it many ethical and legal complications. PublicTechnology talks to digital ethics expert Dr Mariarosaria Taddeo to find out more.

——————————————————–

“Cyberattacks are every bit as deadly as those faced on the physical battlefield.”

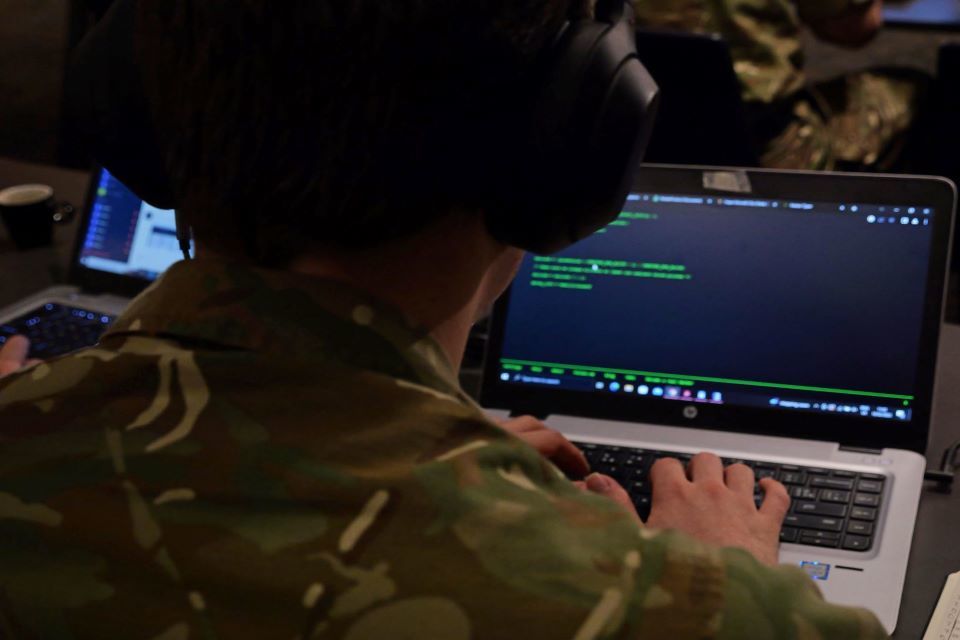

These were the words of defence secretary Ben Wallace last month, spoken on the occasion of the creation of the UK Armed Forces’ first-ever dedicated Cyber Regiment.

The 250 specialist servicewomen and men that comprise the 13th Signal Regiment will be tasked with offering a technical support hub in the UK, as well as securing military communications networks and providing support to overseas operations.

According to the Ministry of Defence, the ultimate goal in establishing the unit is to ensure that “UK defensive cyber capabilities remain ahead of adversaries and aggressors”.

The formation of the Cyber Regiment is far from the first time that politicians and senior military personnel have acknowledged the increasingly important role that cybersecurity plays – and will continue to play – in defence and national security.

One of Wallace’s recent predecessors, Gavin Williamson, spoke in 2018 of his hope that more cyber specialists and other tech-savvy professionals would consider joining the UK’s Reserve Forces – or even pursuing a military career.

“In kinetic warfare, there are infrastructures that are military and civilian. But it can be very hard to draw a distinction in cyberwarfare, because civilians and the military often use similar infrastructure and technology.”

Dr Mariarosaria Taddeo, Oxford Internet Institute

“Warfare is evolving so much and it’s about trying to get a different generation, a different type of people to start thinking: ‘I’ve got something to add to my reserve forces’,” he said.

Williamson will perhaps have been pleased to see last month that the Army wishes to ramp up its efforts to engage with the “online community” through better use of streaming platforms and tie-ins with “urban music influencers”.

Penny Mordaunt, who served as defence secretary between Williamson and Wallace, made an even more significant commitment to technology and technologists when she announced in 2019 that £22m would be spent on establishing a network of cyber operations centres that, the government claimed, would put the UK “at the forefront of information warfare”.

“It’s time to pay more than lip service to cyber,” Mordaunt said. “We must convince our adversaries their advances simply aren’t worth the cost. Cyber enemies think they can act with impunity. We must show them they can’t. That we are ready to respond at a time and place of our choosing in any domain, not just the virtual world. We need coherent cyber offence as well as defence.”

Wallace’s battlefield comparisons, Williamson’s enthusiasm for techies, and Mordaunt’s hawkish rhetoric all speak to the fact that the cyber world is increasingly seen as a potential battleground as much as the physical-world terrains of land, sea, and air.

Dr Mariarosaria Taddeo, a senior research fellow and deputy director of the Digital Ethics Lab at the Oxford Internet Institute at the University of Oxford, tells PublicTechnology that the UK is one among many countries to have come to regard cyber as a military issue.

“NATO and the US recognise the cyber domain as a domain of war; that is an important recognition, and it goes in the right direction,” she says. “When we recognise that cyberspace is a domain of warfare, we recognise that cyberspace has become a key part of our society. And, if cyberspace can be targeted, it needs to be defended.”

As in the physical world, the motive for and perpetrator of cyberattacks differentiate an act of war from an act of crime of terrorism. It is also important to understand where cyber creates a new battlefield, and where it simply adds to long-standing methods of waging war.

“Cyberwarfare is an aggressive action of a state against another state – when we consider ‘cyber warfare’ we are not talking about fighting criminals or terrorists,” Taddeo says. “There is also a difference between cyberwarfare and information warfare, which is a broader concept that covers a lot of different ways of being aggressive – such as propaganda, or radio-jamming signals.”

‘A grey area’

For all its inherent death and destruction, war is subject to clear boundaries, conventions, laws and – if necessary – consequences for those who break them.

The consensus is that these existing frameworks apply to the cyber world too; where attacks wreak the same demonstrable physical damage as would a bomb or a tank, they are understood to be bound by the same treaties and standards – most notably the Geneva convention.

The foremost attempt to catalogue and codify this concept is the Tallinn Manual. It is not a legal document in itself, but an academic project – backed by NATO – that aims to provide a guide to how and where “existing international law applies to cyber operations”.

The foremost attempt to catalogue and codify this concept is the Tallinn Manual. It is not a legal document in itself, but an academic project – backed by NATO – that aims to provide a guide to how and where “existing international law applies to cyber operations”.

Taddeo says that, while the broad recognition of cyber as a potential domain of warfare is welcome, the intrinsic differences between cyber and kinetic warfare ought also to be recognised – and reflected in regulation.

“There is very little regulation, and it has been problematic,” she says. “There is consensus that, where a cyberattack is equivalent to a kinetic attack… and where the cyber domain is used to cause extensive physical damage, the International Humanitarian Law and Law of Armed Conflicts apply. But most cyberattacks will cause disruption to a service or to data; so, they are in a grey area.”

She adds: “In kinetic warfare, there are infrastructures that are military and civilian. But it can be very hard to draw a distinction in cyberwarfare, because civilians and the military often use similar infrastructure and technology.”

The need for internationally recognised regulation or standards is becoming increasingly important as nations adopt a more belligerent approach to cybersecurity.

When the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre was launched in 2016, it characterised its modus operandi as “active cyber defence”. This ethos has since been embraced by the likes of Canada and the US – which has spoken of its wish to “defend forward” against its enemies.

“There has been a slow but concerted shift from the idea of pure defence to a way more active or aggressive approach,” Taddeo says. “There is a growing sense of shifting towards ‘active cyber defence’; which goes from studying an attack and the data to retaliation. I think this is a correct approach – but it is really problematic if this happens in a context where there is no regulation.”

One of the major problems, she adds, is the difficulty of attributing a cyberattack to a definitive perpetrator.

Authorities in the US and the UK are not shy about identifying the four countries that they consider significant hostile actors: Iran; China; Russia; and North Korea.

But pointing the finger at any one of this quartet as the perpetrator of a particular attack is extremely rare.

Taddeo says that “cyberattacks are used increasingly by all sorts of actors” and that, when it is so difficult to indisputably determine the source of an assault, it is dangerous for countries to respond to breaches with retaliatory aggression.

“There is a strong push from many countries to foster an offensive cyber capability and respond to cyberattacks through offensive behaviours – which is understandable, in some regards,” she says. “But they are doing so without a clear understanding of, without internationally agreed criteria to define, proportionate responses, or distinguish legitimate from illegitimate targets. This is all is very problematic, as without international regulation in place offensive cyber may lead to escalation of conflicts more than to stability in cyberspace and security of our societies.”

International law

At the NCSC’s annual CyberUK conference last year, PublicTechnology asked the organisation’s chief executive Ciaran Martin whether he thought an effective cyber Geneva Convention was necessary.

“There are countries that, by and large, behave towards some form of internationally acceptable norms and behaviour – and countries that don’t,” he said. “I think that the prospects of that sort of process (a digital Geneva Convention) taking off at large-scale, intergovernmental level in the short term aren’t very high.”

Martin also pointed out that “international law applies in cyberspace – and the question is how, not if”.

But, if and when international focus turns to the creation of a new law, focused purely on the cyber arena, then the UK would participate in that process, according to the NCSC chief.

“There are countries that, by and large, behave towards some form of internationally acceptable norms and behaviour – and countries that don’t.”

NCSC chief Ciaran Martin, in April 2019

“If, over time, the conditions are right and something happens, I’m sure the UK would be up for that sort of discussion,” he said.

Taddeo agrees with Martin’s assessment that any kind of worldwide initiative is still some way off.

“It is likely to be solved first on a regional basis before it is solved at a global level,” she said.

Although cyber has become recognised as a domain of warfare, we are yet to see a war that would be recognised as such waged purely in cyberspace.

“I do not think we have seen cyberwarfare – we have seen state-run or -sponsored cyberattacks,” Taddeo says. “The future of war is hybrid warfare, where we have all of the different domains – the kinetic, the cyber, and propaganda.”

There is a well-used military phrase that encapsulates the perpetual uncertainty of life as a soldier at war – a single component of a huge conflict, for whom it may rarely be clear which side is winning, nor why.

‘The fog of war.’

The dawn of cyber warfare will, according to Taddeo, do nothing to unshroud the battlefield.

“It gives more opportunities to support and plan operations, but it also makes it harder to foresee and plan against incoming attacks,” she says.

“It makes the fog of war much thicker.”

Click here to read more about Dr Taddeo’s research

This article is part of PublicTechnology’s Cyber Week, a dedicated programme of content focused on the threats facing the public sector and the country at large, and how government can best respond. Throughout the week, which is brought to you in association with CyberArk, we will publish interviews, features, analysis and exclusive research looking at – in chronological order – the cyber landscape for defence and national security, businesses, citizens, the NHS, and, finally, central and local government. Click here to access all the content in one place.

Mexican Easy Pharm: mexican rx online – Mexican Easy Pharm